Telling Your Project's Story to the Judges

By Tessa Alexanian & JC Gray

Almost every one of the iGEM medal criteria begins as follows: “Convince the judges…”

But how?

The judges aren’t trying to be mysterious—you can read the same medal criteria, rubric and handbook that we do. Still, when I (Tessa) was on an iGEM team, I wasn’t really thinking about the judges as people, who would have a particular experience of my project and presentation.

JC and I hope this post will help you understand how to communicate with the judges. We’ve based this advice on our years of judging at iGEM, but it’s intentionally just our perspective. Every judge uses their own best judgement to assess projects. You can read the perspectives of other judges elsewhere on the iGEM blog; check out My First Time as an iGEM Judge or Judging in iGEM 2020.

Tessa getting ready to present at the 2014 jamboree. She knew she needed to impress the judges, but hadn’t thought very much about what that would mean. Photo Credit: Waterloo iGEM 2014

Your wiki is your first (and last) impression

Judges start learning about your project by reading your wiki. Then, when we’re filling out our judging ballots, we look over the wiki again to make sure we’ve remembered everything right. So what does this mean for how you tell your story?

1. Let each page stand on its own.

When we finalize our scores for each special prize, we’ll go directly to your dedicated page for the prize. If relevant information is elsewhere on your wiki, we might not see it.

It’s okay to repeat data and figures across pages, but don’t copy and paste whole paragraphs of text. When a result is relevant to multiple prizes, recontextualize the data or figures to reflect the topic being covered in each page. This will also let judges know that the result is published elsewhere on your wiki.

2. Make it easy to navigate.

This applies both across the wiki as a whole and within each page.

As a whole, you want to make it easy for us to get an impression of your project when we’re first reading through the wiki. What was your main idea? What were your big results and accomplishments? What parts of your project didn’t work or weren’t yet tested?

Within pages, think about a judge skimming through your wiki trying to answer a really specific question like “did their choice of ethanol assay make sense?” or “was this the team that ran an art show?” Can we find that answer easily?

3. Help us interpret your results.

Your judges are master generalists; and chances are more than one of us won’t know the details of your project’s methods. Please use visualizations, label your figures with a lot of context, and otherwise help us to interpret your results. We’ve often seen pictures of gels or plots that just don’t have enough surrounding information for us to know what they mean.

The interpretation can also be a part of the story: why did you run this particular experiment or model? How does this graph, or equation, or photograph tie back into the overall story of your project?

Your poster contains your most important results (scientific and beyond)

Unlike your wiki, your poster doesn’t need to document your whole project. It really just needs to document your most important results, like constructs made, models analyzed, hardware built, and human practices insights. Work that didn’t lead to key results (often things like collaborations, outreach, or modelling experiments) can be left out. How should you design your poster?

One of the nominees for the 2019 best poster award, from the Wageningen team: https://2019.igem.org/wiki/images/5/56/Wageningen_UR_Poster.pdf

1. Pick your most important results.

Think about what you’ll talk about when you give someone a two-minute pitch for your project. Is there any evidence you’d want to gesture to as you’re talking? Put that on your poster.

One of the items on the rubric is “How well does the poster communicate the team’s project and their goals?” All of the results on your poster should be linked to your project’s overall story and goals.

2. Find visual evidence for those results.

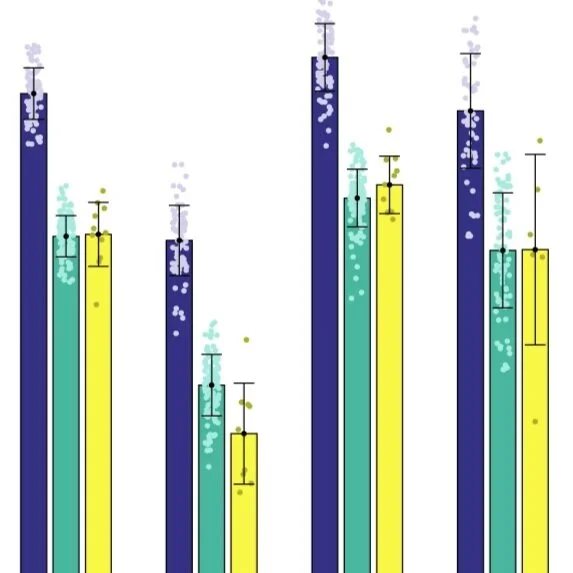

Because your poster might be viewed on a small screen (or from a distance, when we have a physical jamboree) you should look for visual evidence that supports the key results and outcomes of your project.

This could be photographs, graphs, flow charts, diagrams… You can get creative! On the Wageningen poster, there are pictorial synthesis pathways, photographs of centrifuge tubes, graphs of fluorescence, and many more kinds of visual evidence.

3. Label and contextualize your evidence.

Your poster should mostly present visual evidence, but you need to provide detailed labels and context for it. This will probably require a general introduction to the project and your methods. Make it clear how each piece of evidence contributes and connects to your project’s story.

On the Wageningen poster, the team shows interviews from their Human Practices beside various sections, as well as pop-out boxes showing the constructs they built. That said, there was one set of graphs (the bacterial load heatmaps in the lower right) where we would have benefitted from a bit more context.

4. Arrange it logically and smoothly.

Someone should be able to understand your project just from reading your poster. Arrange your visuals and contextual information so that they flow logically and smoothly when read. You’ll need to consider font readability, whitespace, and other graphic design choices. The Poster Design Resources on the iGEM wiki might help.

Your presentation is your narrative

What do you want judges to remember about your project? Where do you want your audience’s attention the most? Your presentation is your chance to craft a narrative experience of your project; help us get excited about your work! This year’s video presentations are a unique opportunity, as your video will be linked from the iGEM 2020 website and could even go more publicly viral. There are also a host of new and interesting styles to try out in your videos―no longer are you bound by stage presence and powerpoint slides!

Let’s think about what goes into a great presentation.

1. Use inspiration to find your presentation’s voice.

Look up great examples of presentations or lecturers that you enjoy and think about why they are so effective. Is it the tone? The pacing? The structure? Do you and the speaker have a similar sense of humor? If there are data, how do they smoothly convey it? Hopefully you and your team have common inspirations and can use them to create a vision of how you want your presentation to feel.

Here’s some of our picks for amazing presentations with a mix of styles:

High tech explained simply

Ellen Jorgenson: What you need to know about CRISPR

Grounded tone with personal reflections that captivate

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: The danger of a single story

Fun, poppy, and humorous

Crash Course Computer Science: Early Computing

2. Distill your story to its essence.

One you have a vision, the next step is to script your presentation video. You’ll need a complete script, since you’ll be submitting subtitles along with your video. Your presentation will most likely have to leave things out to keep it paced well, and that’s okay! It's better to tell the story of a few results really well, so that you're sure the judges will understand them, than to make a cluttered and rushed 20 minute presentation. Be confident and tell us judges to look something up on your wiki or talk to you about it at the poster session if you feel so inclined.

3. Hold the audience’s hand.

When making your slides and script, ask yourself “what is it that I want my audience to know or feel from this content as soon as I’m done speaking?”

You’ve been living and breathing and not-sleeping your project for months, but judges are only just learning about it. Help us understand how all the graphs and gels and plasmid maps fit together. What part of the overall story of your project is each result telling?

4. Do a dry-run of the live interactions. Seriously.

Imagine you and your team, relaxed and confident, before your presentation slot in November 2020. Of course with social distancing, a gathering such as the one shown in this image of a team gathering at the 2019 Giant Jamboree is not possible, but do your best to capture the essence of being together.

Photo Credit: Justin Knight and the iGEM Foundation

In a normal year, we’d tell you to run through your presentation 20 or more times, and to have back-ups in case you run into slide issues, but these issues matter less in a world of pre-recorded presentation videos. However, you should still practice what it’s like to talk and present over a computer webcam, and think about how you’ll handle unreliable Bluetooth or WiFi when interacting with the judges.

Are you and your teammates on the same wifi (what happens if it goes out)? Is your microphone reliable? Is there a plan for who will fill in in case of technical glitches? Are you confident that more than one person could adequately explain multiple parts of the project?

Test your chosen computers and networks on the video-hosting platform of choice (when announced), and make sure there aren’t little bugs waiting to ruin your time interacting with the judges.

And hey, things happen. Have grace when something goes wrong and try to give us judges a good experience no matter what. The reason for needing to practice for the live stuff is because...

5. The Q&A is a symbiotic part of your presentation and project.

Practice the Q&A. As a judge, we have seen many impressions of a team seemingly hinge on how well they answered questions, sometimes even a single one. Not that this should concern you too greatly! However, the Q&A portion of the competition should not be thought of as an afterthought whatsoever.

Before the jamboree, show your presentation video or script to everyone you can think of and record the most commonly asked questions. Study up on the best answers you can give to those questions. If you left information out of your presentation (maybe purposefully!), you may want to have a slide or wiki link prepared to send to judges who ask about it. Also...

6. Don’t be afraid to say what didn’t work.

When we as judges ask you about something that maybe isn’t your project's strong suite-- be transparent about the shortcomings if you know they exist! Hearing about troubleshooting is often how we see that you really understand the problem, the bacteria, differential equations, and such that you worked with. Also... c’mon, not every experiment worked. Judges know this stuff happens (it’s actually likely that at least one judge on your panel has a postgraduate biology degree and has experienced a multitude of experiments not working). We will be much more impressed with a well-documented negative result than an overhyped positive one. Self-reflection on your failings lets the judges more deeply appreciate your iGEM experience, regardless of the outcome.

7. Be more than a sum of all your slides.

Finally, show us the elements of your project (wet lab, outreach, modelling, software, human practices, measurement) in harmony, not in isolation. We recommend not creating rigidly separate sections for things like kinetics modelling, education, and human practices, etc., because you risk the story becoming disjointed and disconnected. Instead, work to seamlessly weave what you learned from those things throughout your entire presentation where it makes the most sense. Consider, for example, the Human Practices Cycle:

The HP Cycle - https://2020.igem.org/Human_Practices/How_to_Succeed

How can you possibly put all of these moments of HP work on a single slide at the end of your presentation?! Trust us―show the work and help us move logically from your problem to your wetlab, to your hardware, to your expert interviews, and we will see all of it for what it is and give you the medals you deserve. When you show the judges how all your work ties together, it’s much easier for us to understand your project, and often much more impactful on us as viewers.

If you are worried about leaving any doubt about your medal qualifications in your presentation, remember that it is perfectly fine to have your wiki organized by section and category. You may completely lay out what you did and did not do on either your poster and/or wiki and we will include it in our judging.

We’re looking forward to your stories

After the jamboree this year, all the judges will take what we learned from your wikis, posters, and presentations, and enter scores into our judging ballots. Each ballot has three sections: the medal section, where judges select the medal your team qualified for; the project section, which is the most determinant of which teams are nominated for track and grand prizes; and the special prize section, where each prize is scored according to its own rubric.

It’s not all evaluation―judges love talking to each other about all the interesting science we’re learning about, as evident in this photo of judges talking with one another at the 2019 Giant Jamboree.

Photo Credit: Justin Knight and the iGEM Foundation

Each team gets their own ballot; you’re not judged relative to other teams. Our ballots are not a judgement of how interesting your project was or how hard your team worked. The scores simply reflect how well we think your efforts fit the categories on the rubric. Your score matters, sure, but it can’t possibly reflect all the things that matter about iGEM.

None of the judges (that we know, at least) volunteer for this because we love being judgemental. We do it because we love being a part of the iGEM community, and are excited to meet people who are as obsessive and enthusiastic about synthetic biology as we are.

You’re a part of that community, too. Let’s be excited together! We can’t wait to hear your stories.