Designing Scientifically Valid Surveys

by Matthew Sample and JC Gray

on behalf of the iGEM Human Practices Committee

Matthew and JC also gave a session on this topic at iGEM’s 2020 Opening Weekend Festival (YouTube)(Bilibili)

Surveys can provide you with valuable information that can augment your iGEM project’s design and impact. They can, for example, help you understand if your project will be met with excitement or skepticism by the communities you want to help. Although surveys may seem simple and straightforward, they are often challenging to execute well. Surveys are a form of experiment, and like any experiment, they can be designed and implemented poorly. A poorly designed survey will give you ambiguous results, or worse, will bias your responses. In this post, we will share some starting points for designing and conducting useful surveys.

A helpful way to frame surveys is through 3 Rs of Human Practices:

Reflection – Ask yourself why you are doing this project. What is it in your personal life or in society that is driving you? Don’t forget to reflect on your early assumptions or strategies throughout the season too, especially at the end.

Responsibility – If you are going to do a survey, then it is your responsibility to execute the survey to the best of your ability so that it has maximum value. If you cannot faithfully execute a survey that has a good plan for distributing to a representative sample, for example, it is also your responsibility to note these inefficiencies and tailor your expectations or analysis accordingly.

Responsiveness – If you believe the survey has unearthed something important, you must incorporate the data from the survey into your project in a meaningful way. Show us that what you learn is of tangible value to your project’s story. This responsiveness quality is what proves that your work is not in isolation, and lends credence to your project overall.

In communicating your iGEM project and its impact on the world, you are essentially telling a story. It is important to realize that your human practices work, including any survey that you do as a part of your iGEM project, is critical in selling the story that you are telling.

“What kind of story are we telling? Is it one of love?”

With that as background, let’s go through the steps involved in designing a useful survey.

Step 1: Form a Hypothesis

Like all good science, designing a survey begins with the formation of a hypothesis.

Tip!

Understand whether you are trying to know more about the problem and its’ complexities or you are trying to get feedback about a solution you are hoping to implement.

At this time, you probably have a good idea about the problem you want to solve, and you may have an idea about the type of solution in mind. Even so, you need to give yourself more than one shot on goal in in both understanding the problem and its’ complexities and intricacies, and then designing a solution that will answer all the different ways that you want the problem to be answered.

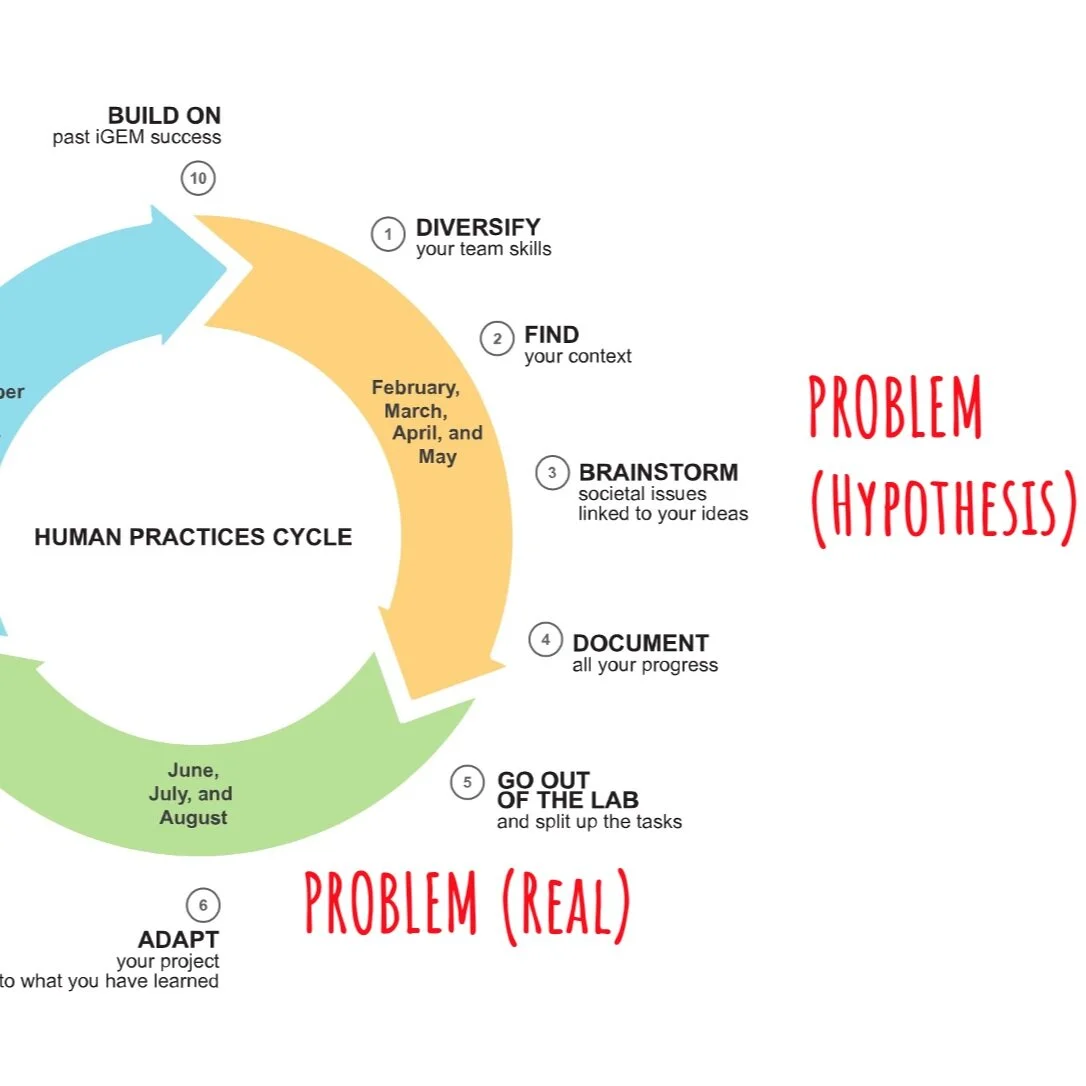

Think about the Human Practices cycle iteratively, going through the cycle more than once so that you have chances to prototype. This is where having a hypothesis is useful, because testing your hypothesis will let you come to a better solution. Although you may have a good idea of the problem statement now, there may be societal, political and cultural intricacies that you will discover as you go through the process of testing the assumptions in your hypothesis.

Your solution is actually a hypothesis of what you think the solution should be. When you test the assumptions in your hypothesis, you will arrive at different ways your project can be improved because you will discover things that you did not know about when you began your project.

Tip!

Rewrite your project as a series of hypothesis

What are your assumptions?

What is testable about your assumptions?

How could you test it?

Step 2: Choose a method

There are many methods for obtaining information, with various pros and cons, and you may use more than one method to gather the information you are looking for in your project.

For example, a good first step is to conduct some drylab research (e.g. databases, software) to find out what has already been studied in your area of interest. Querying academic literature databases such as Google Scholar (or equivalent) or your University Library enables you to build from existing research literature. By consulting the academic literature, you may find existing data that you do not need to collect again (hence saving time) and you can learn how to conduct surveys by studying examples from experts who are published in the area. And even if you decide not to conduct a survey, the research literature you discover will help you strengthen your project design.

It’s important to realize that research methods have the potential to cause harm. Personal information or data you collect may be sensitive, even if “anonymized”. Some people are especially vulnerable to harm from data misuse, such as children (who may not understand and did not really give their permission), marginalized groups (who may be targeted), etc.

Tip!

Ensure your method is ethical (and don’t break the law!). Before moving forward, ask whether your survey/interview/focus groups put participants at any risk.

At a minimum, you will need to obtain Informed Consent. Before engaging anyone in a survey, you must provide them with information about what the survey is and how you are going to use their data, and ask them in a free way if they want to participate or if they have changed their minds.

Most countries have federal or regional laws about how to conduct social science research. As an example, the United States enacted Public Law 93-348 – the National Research Service Award Act of 1974 – which requires that research ethics guidelines be followed when doing research with humans, such as collecting data on gender and health status.

Tip!

Do not copy the informed consent form shown above. Every institution and country has different guidelines for how to build an informed consent form for your survey. It’s important for you to contact your local research ethics board or research ethics authorities and ask them what the guidelines are for your institution in your country. To find out about your university and national guidelines, try doing an internet search using the name of your institution and the keywords “Institutional Review Board” “Research Ethics Board” or “Social Science Research Ethics.”

One of the most frequently asked questions at Human Practices is about how to determine if your project and/or survey requires institutional review board, or IRB, approval. The answer from Human Practices is simple: if you have to ask at all…you probably need to be asking your relevant IRB (or equivalent). It not possible nor proper for iGEM or its volunteer Human Practices Committee to determine if your scientific activities require any ethics approval and so that question can only be definitively answered by the appropriate IRB or equivalent body directly. Once you loop in an official contact from that type of body, you should consider them a valuable point of contact for most questions regarding your project’s compliance.

Step 3: Design your research

Once you have done some background research, chosen survey as the method you will use for gathering information, and have run an ethics check, then you are ready to design the outreach for your research. In your design you will need to consider Psychometrics – a field that combines psychology and metrics – to learn how you can collect the cleanest data from people who can have altered moods. Realize that in conducting a survey you are trying to translate the thoughts and opinions and feelings of people which can be transient or totally different from one day to the next, and you are trying to learn about a population and quantify that information in a meaningful way.

In designing your survey, it is critical that the language you use be as clear as possible so that you can avoid unreliable and unvalidated results. The use of clear, concise, and non-confusing language is important for any and every language you choose in designing your survey.

Tip!

Be wary of survey translation tools. One of the pitfalls to watch out for is too much reliance on translation tools for translating your survey into other languages. If you wish to survey an international community, you should seek help from others who can help with the translation(s) so that the language(s) are clear, concise and not confusing.

Some guidelines for designing your survey include:

Be objective and dispassionate when wording the questions (e.g. do not use words such as me, my, we, ours). The relationship between the survey respondent and the person distributing the survey might bias the results (e.g., the survey respondent may not want to appear confrontational)

Poor question: “Do you think your friends would like our jackets?”

Better question: “Would you recommend these jackets to others?”

Be exclusive and exhaustive with the options you give to people in responding to your survey. Have clear categories for each of your questions so there is no overlap (e.g., do not include options such as “don’t know” or “doesn’t apply”)

Poor options: “When do you usually eat lunch?”

1) Before noon

2) After noon

Better options: “When do you usually eat lunch?”

1) Before 11:00 AM

2) From 11:00 am – 1:00 PM

3) After 1:00 PM

Use an odd number of responses (e.g., yes, no, maybe) to allow room for a neutral opinion to shine through. Allowing survey respondents to indicate a neutral opinion is still good information because it means that something is not important to them.

Example: “Please rate the following statement: This webinar is helpful”

1) Strongly Agree

2) Agree

3) Neither Agree or Disagree

4) Disagree

5) Strongly Disagree

When asking a question with options that cover a spectrum, anchor your response on a scale (e.g., 1 = worst, 5=best)

Example: “Please rate your experience staying at the hotel:

1 (terrible)

2

3

4

5 (great)

Give a balance of positives and negatives. You want to make sure you are giving the survey respondent permission to complain. You do not want to not ask a question that could get at a deeper feeling the respondent might be having. In the example below, the option to “Please Explain” gives the survey respondent room to complain or to highlight something. You are not directly asking for this information, but are inviting your survey respondent to add more information into the conversation.

Example: “Please rate the following statement: During the project, I felt very supported by my team”

1) Strongly Agree

2) Agree

3) Neither Agree or Disagree

4) Disagree

5) Strongly Disagree

(Optional) Please Explain

Consider the length and the relative difficulty of completing your survey. You are trying to learn about a problem at the community level and you want to be sure that those completing your survey represent a truly randomized sample. Answering dense paragraph-long questions or a long list of questions can be really taxing, leading to low response rates or incomplete survey rates. More substantial surveys typically require that the survey respondents have a vested interest in the topic or are offered an incentive.

Tip!

Keep your survey under 5 minutes (ideally 2- 4 minutes) and make your questions easy and short.

Ultimately, your research design is going to come down to sampling. Sampling is one of the most important areas that will either justify all the work you have done or completely ruin it. Your sampling is going to allow you to do what surveys are meant to do, which is polling people for their opinions about a single subject with good statistical power. If you craft your survey well and are careful about your sampling, you might even be able to assess the relationships between two things.

When you are trying to describe an entire population, consider whether your sampling is random. For example, are you selecting only for people with internet access? Or limiting your sampling to only those people in your institution? These sampling techniques may be valid, but you’ll want to consider ways in which sampling may limit your analysis. Finally, consider what you will control for in your sample. It is generally good practice to take some demographic data, such as race, gender or income (pending ethical review), and control for that in your sample.

Step 4: Deploy and Analyze

Before launching your survey, you’ll need to do one final check which is to make sure people understand your survey questions. Surveys developed by iGEM teams can sometimes be really excruciating to take if the survey respondent is not on an iGEM team or is not familiar with iGEM. Questions to ask yourself include:

Is there too much jargon?

Do people actually care about the content?

Is the subject matter of the question(s) unfamiliar or sensitive?

Cognitive pre-testing is a formal method you can use for checking that your questions are well-written and appropriate to test your hypothesis. For example, using a technique known as “think aloud” you have people take the survey along with you (e.g., on Skype or Zoom) and ask them to tell you what they are thinking as they answer the questions. By asking “What does the option you chose mean to you?” and observing their response, you can then check that their answer is the same as what you intended. If they look really upset, then you’ve probably done something wrong. When pre-testing your survey, it’s a good idea to start with team members or friends since they are not part of your official sample.

Tip!

Give yourself more than one shot at pre-testing your survey. Ask an expert (maybe a sociologist or a specialist related to your project topic) to take a look at your survey. Have a few people at your institution take the survey. Consider doing a short beta-deployment to see what types of responses you get. Consider trying different platforms (e.g., Survey Monkey, Qualtrics, Unipark, etc.) to see what fits with your workflow, what analysis features the platform offers you, and what convenience features the platform offers your survey respondents.

Your analysis of the results is the final and most important part of the survey because it ties everything together. When analyzing your results, consider whether you can use statistics to describe or compare a population. Can you cluster your survey respondents’ thoughts and opinions into categories? And…. something that eludes many iGEM teams … can you analyze your data in a statistically meaningful way?

Finally, if you find a null result or something that is not statistically significant, don’t be discouraged by the analysis you can do with that. It may not seem that exciting that you didn’t unearth something incredible or totally unexpected, but you can justify why you believe your valid results show that something was not of importance to the people you were working with on your project.

In summary, you can tell the story of your iGEM project using good Human Practices and (if appropriate) carefully designed surveys. In designing your survey, it is important to:

Clarify your hypothesis

Choose you method carefully

Follow local ethics guidelines

Use best practices in survey design

Be honest with analysis and results

Please don’t hesitate to reach out to us at humanpractices@igem.org. We are always happy to answer your questions and want to be resource for you in this incredible iGEM year. Thank you!