Between you and the world: Maintaining balance between your science and the stakeholder

by iGEM Human Practices Committee members Jordan Hartunians, Julie Trolle, Melody Wu, Shrestha Rath, Tessa Alexanian, and JC Gray

Jordan Hartunians also gave a session on this topic at iGEM’s 2021 Opening Weekend Festival

(iGEM Video Universe)

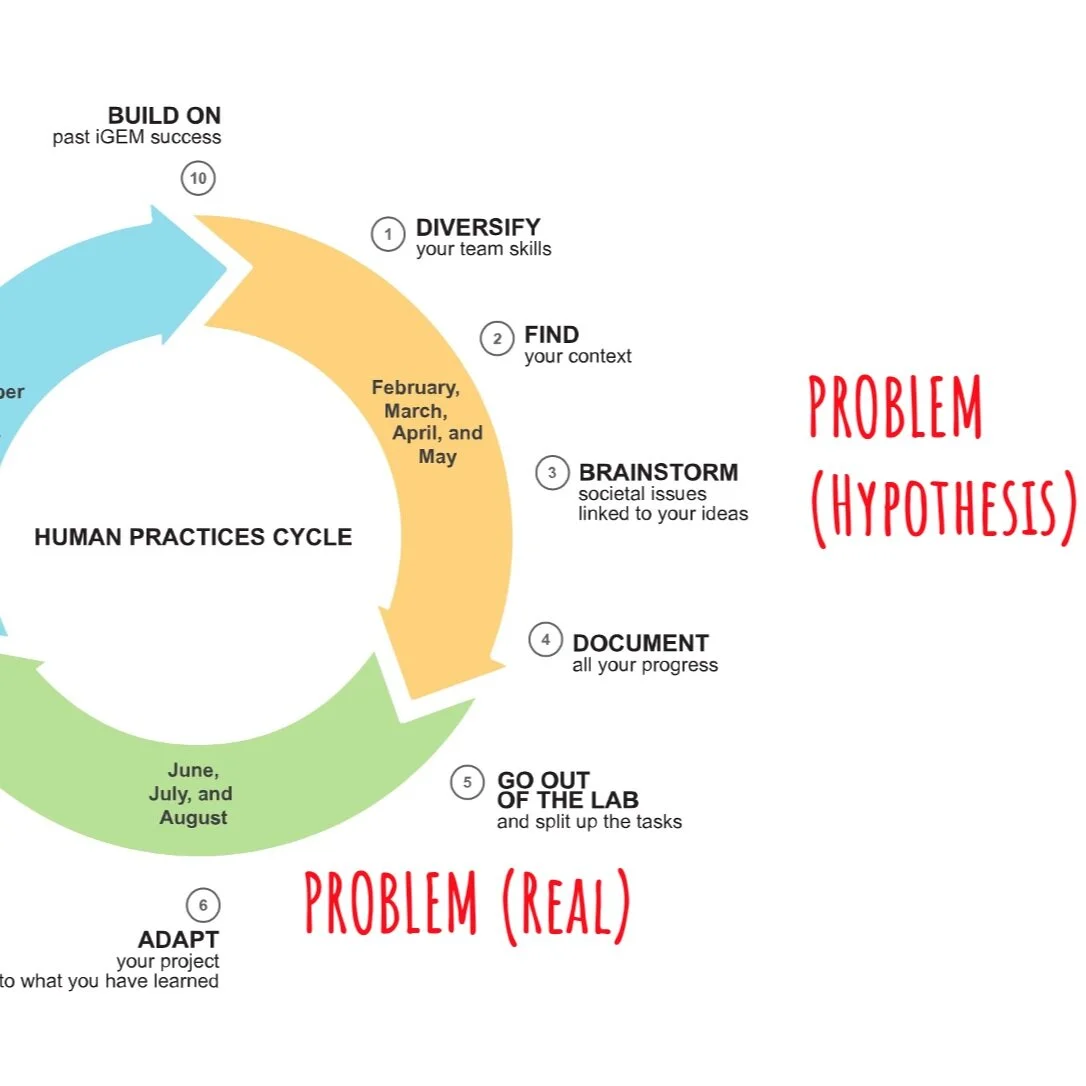

Synthetic biology has unveiled a world of potential for improving the society around us. In recent years, genetic engineering tools have enabled the development of low-cost diagnostics platforms, personalized medicines, and environmentally-friendly chemical manufacturing processes. However, it is not always straightforward to know what societal problems to tackle or how to tackle them. The value of a project will depend on its specific context and the stakeholders within that context. The act of giving consideration to these factors is part of what we at iGEM refer to as Human Practices (HP). In this post, we on the HP Committee would like to share our thoughts on integrating stakeholder views into your iGEM project.

Kinds of Stakeholder Engagement

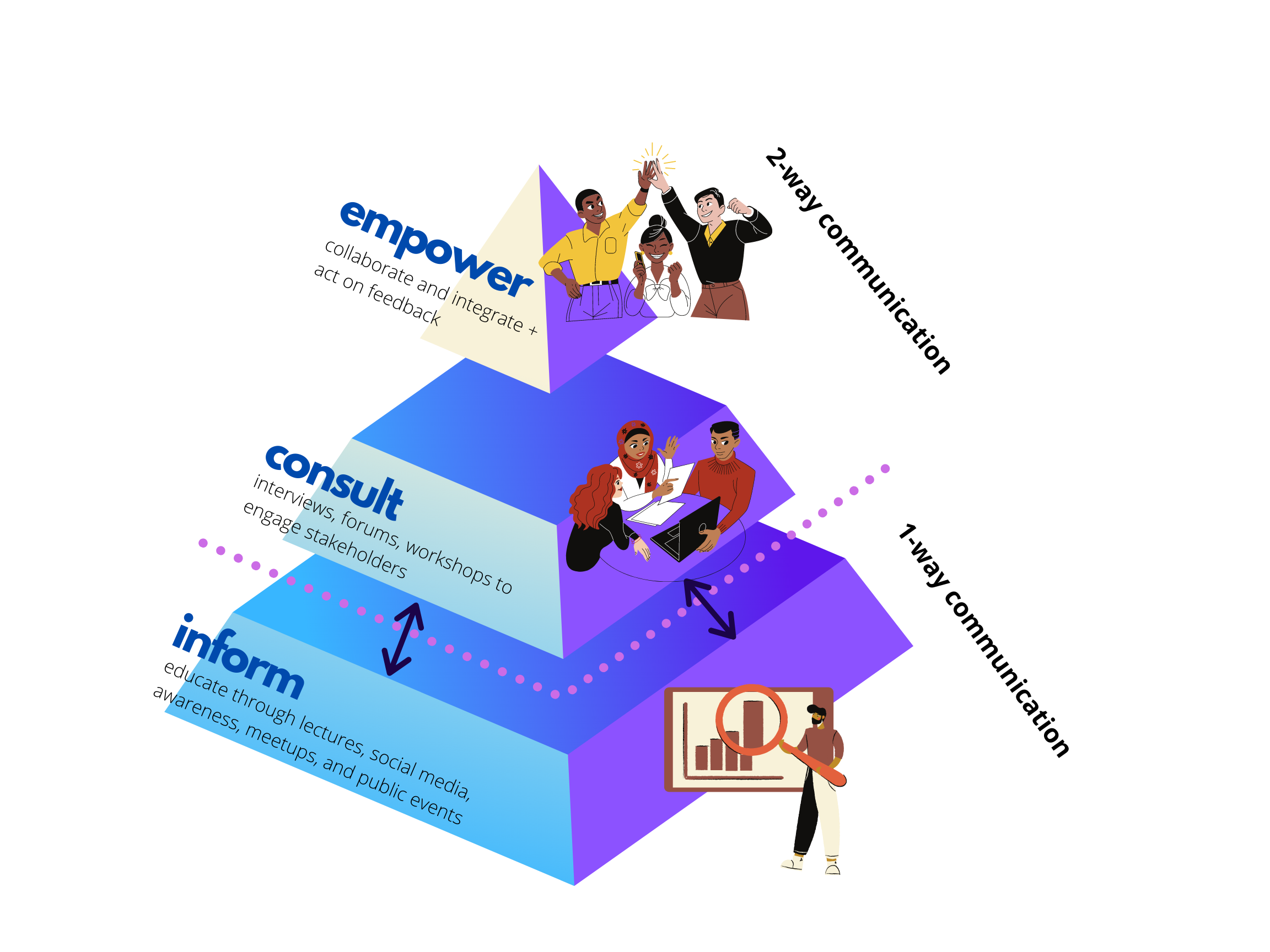

Engaging with stakeholders directly, and then reflecting on the feedback they provide, is a good way to effectively integrate Human Practices into your project. There are multiple ways to go about engaging with stakeholders. To begin, it’s important to make a distinction between 1-way and 2-way stakeholder engagement.

● 1-way engagement describes a unidirectional flow of information when interacting with stakeholders (in short, informing)

● 2-way engagement describes a bidirectional style of communication where both researchers and stakeholders consult with each other before proceeding to work on potential solutions (in short, consulting, involving, and collaborating). During consultations, researchers are enabled to act on suggestions provided directly by stakeholders such that the research outcomes can maximally benefit both parties.

Image created by Melody Wu, inspired by Bellucci, Biagi and Manetti (2018), using design tools from Canva

Though this distinction sounds rather binary, the reality is that stakeholder engagement often falls into a grey zone between the two approaches. For instance, putting on a public art exhibit related to your project, like Team Montpellier 2018, could be a creative way to inform the members of the public about synthetic biology (1-way engagement) or it could be a way to gather and incorporate their views on the project should move forward (2-way engagement).

It is also important to not confuse human practices-driven stakeholder engagement with market research-driven stakeholder engagement. Human Practices should help you gather real-world arguments for taking your project in a particular direction. Although the data you collect may also help attract funding opportunities and refine marketing strategies, Human Practices should involve deeper questions about the value of your decisions rather than their mere utility for developing good marketing. You can see an example of this in the detailed user research conducted by Team Valencia UPV 2018.

Team Valencia UPV 2018 divided their Integrated Human Practices into 3 parts: Kano model, Expert Dialogue, and Safety Design.

For example, surveying what price a potential customer (the stakeholder) would be willing to pay for a novel device could have the purpose of determining (i) how valuable your business venture is or (ii) what price is suitable so the device can be most impactful to those who need it. The practice of gathering pricing information is the same but the intentions, and perhaps the conclusions drawn, are different. Only the latter seeks to place the stakeholder’s needs and views at the center of the interaction. With this type of framing, your team may more naturally incorporate deeper inquiries into the particulars of your stakeholder’s needs, in which price is but one detail.

As you discover who your stakeholders are and what their values are, continuously grade your interactions on the quality of the exchange, and seek to maximize 2-way communication in frequent and creative ways throughout.

Where things go wrong: Pitfalls of not getting outside views

Human Practices have been given consideration by researchers for several decades yet there are countless historical examples of a lack of external engagement in scientific projects that could have or indeed have endangered our societies. Even today, plenty of projects fail to consider the concerns of the public.

Example 1: Reconstructing the Spanish Flu virus

The US Center for Disease Control reconstructed the “Spanish Flu” virus from the 1918-19 pandemic in the name of understanding pandemics and developing antiviral therapeutics, but details of the reconstruction process were published for anyone to read - both good actors and bad. Ethicists, biosecurity experts, and stakeholders could only later condemn the decision to publish at which point the damage could not be reversed. Had broader consultations been done with stakeholders prior to the publication, the knowledge, which has the potential to enable a devastating biological weapon, might have been handled more carefully.

Example 2: Daisy drives in New Zealand

Another good example is the story of daisy drives and the plan for their implementation in New Zealand (Aotearoa). Researchers developed a new technology, the gene drive, which allowed for the eradication of invasive species via genetic systems designed to spread rapidly through the invasive population. Scientists anticipated that such systems could become invasive themselves, and developed the daisy drive, a system based on a genetic “fuel” that exhausts along the generations, theoretically preventing indefinite spread of the effects through global ecosystems. However, setting aside the remaining ethical question of whether it is right to introduce a system thus far only deemed to be safe in theory into nature, the project directors failed to engage with local stakeholders while planning for the first real-world implementation of the daisy drive in New Zealand.

The idea, spearheaded by researchers from New Zealand and the US, was to propose the use of daisy drives to help make New Zealand predator-free and eliminate populations of invasive rats, stoats, and possums by 2050. While the project originally intended to consult with the local Māori population to better understand the interests of the local population, those partners were not invited to amend the resulting manuscript, and thus were not able to add their voice to the conversation. Melanie Mark-Shadbolt, a Māori biosafety official, argued that this paper was “self-indulgent in that it unashamedly pushes for the use and consideration of their research”, that the authors did not consider any political implication of such a publication, and that external partners such as the authors could not grasp the complexity of implications such an intervention would have on the local ecosystem.

Kevin Esvelt, responsible for this manuscript, later acknowledged the importance of engaging with local stakeholders: “This is precisely why Māori co-governance of daisy drive development is necessary if the method is ever to be used in Aotearoa: I know as little of the local ecosystem as I do of the local politics, meaning that I cannot possibly evaluate the likely consequences. It is why the matauranga Māori, the wisdom and way of knowing of the Māori people accumulated over generations in Aotearoa, will be essential to help ensure that any action taken is in the best interests of the taonga species.”

Example 3: Lack of inclusivity in genetic testing

Inclusivity is thus an important aspect of HP considerations. Concerns regarding the lack of inclusivity have also been raised more recently in the field of human genome sequencing. 23andMe is a company which allows users to submit their DNA for genetic testing to screen for genetic markers that indicate a heightened risk of various health conditions or other genetically determined traits. Though the company was founded over a decade ago, CEO Anne Wojcicki described their product as “euro-centric” as recently as last year and lacking in accuracy when testing Black individuals, due to the underrepresentation of their genomes in studies and databases.

23andMe’s competitors Ancestry and Nebula Genomics have also acknowledged a similar lack of inclusivity in their data. Such disparate outcomes could have been avoided had certain measures had been adopted. Experts have proposed increasing transparency when communicating genetics research to concerned and underrepresented populations and encouraging their recruitment to participate in research to gather more adequate data.

These stories illustrate the impact that engagement with concerned parties can have on HP issues. They show the importance of not only exhibiting a willingness to consult with the proper stakeholders, but ensuring a 2-way exchange of information, where the voices raised are listened to. Real-world projects that did not engage in a 2-way manner with interested parties are numerous, and it is easy to argue that such efforts are likely to be time-consuming and costly. However, to realize the full potential of the technologies under development and to optimize societal outcomes, HP must be given consideration, and engaging with stakeholders in a 2-way manner is more often than not an effective way to do so.

Identifying relevant stakeholders

How do you know who the stakeholders relevant to your project are? Consider all parties who may be affected by your work or who may have a particular expertise to identify the potential outcomes of your work - anyone who has a direct or indirect “stake” in your project. This list may include but is not exclusive to scientists in and outside of your field, regulators/government officials, local community representatives, industry representatives, and even members of the general public. Some would even argue that non-animate subjects such as the environment can be stakeholders.

The Rockefeller Foundation has laid out a framework for mapping stakeholders to allow the researcher to best understand how to helpfully engage with various stakeholders. A helpful place to start could be to map out all your identified stakeholders according to how relevant their expertise is to your project, what the nature of their expertise is as well as the strength of their interest in your project. This should allow you to understand if you have captured a diversity of perspectives amongst the stakeholders you have reached out to and can furthermore inform how you choose to engage with each stakeholder (informing, consulting, involving or collaborating).

Image from Gather: The Art and Science of Effective Convening. Copyright © 2013 Deloitte Development LLC. This publication may not be modified or altered in any way.

Another idea could be to classify stakeholders into larger categorizations and then identifying more specific groupings or representative individuals from there. For example, the 2020 iGEM team from TU Delft performed a highly systematic identification of stakeholders and reached out to stakeholders that were categorized into three major groupings (Science, Industry, and Civic Society) in their effort to develop a novel bacteriophage-based biopesticide to control populations of desert locusts. Within those categories, they spoke with end-users (local locust control experts), farmers in areas affected by locusts, regulators, the public at large as well as scientists from a diversity of fields including but not exclusive to bacteriophage experts, plant pathologists, entomologists, bioethicists, and biosecurity experts. Their approach helped them gain a holistic perspective on their idea and were, as a result, persuaded to shift their course of action from preventing locust swarming to actively killing locusts. They were thereby enabled to conduct scientific research that was deemed more likely to be more effective by relevant stakeholders.

In your search for stakeholders, we recommend being systematic and thorough in your search. Be sure to not only identify stakeholders who are easily accessible to you (such as your PI or your friendly neighbor’s company) but also make an effort to think of stakeholders who are most relevant to your project. Additionally, be sure that you reach out to a diversity of stakeholders - people of all relevant backgrounds and expertise. This will most likely improve your understanding of your project and its role in the society around you.

How to implement stakeholder engagement?

Imagine, your team has done a wonderful job identifying all relevant stakeholders related to your project and now that you understand the role of 2-way engagement - how do you go about interacting meaningfully?

(1) Stakeholder interaction when defining problems and questions

Engaging stakeholders early on - while you and your team are defining your project’s questions - can provide a real picture of the practical context of your research and the issues facing those who work in that context. Not only does early consultation with stakeholders build trust, but this effort also helps you to strengthen the application of your work and allows you to dramatically change your course of action early on if necessary. From inviting stakeholders to present and discuss issues related to your research area to asking for input by informing about your upcoming research project via social media, this 2-way flow of information roots your research problem firmly in real-world context.

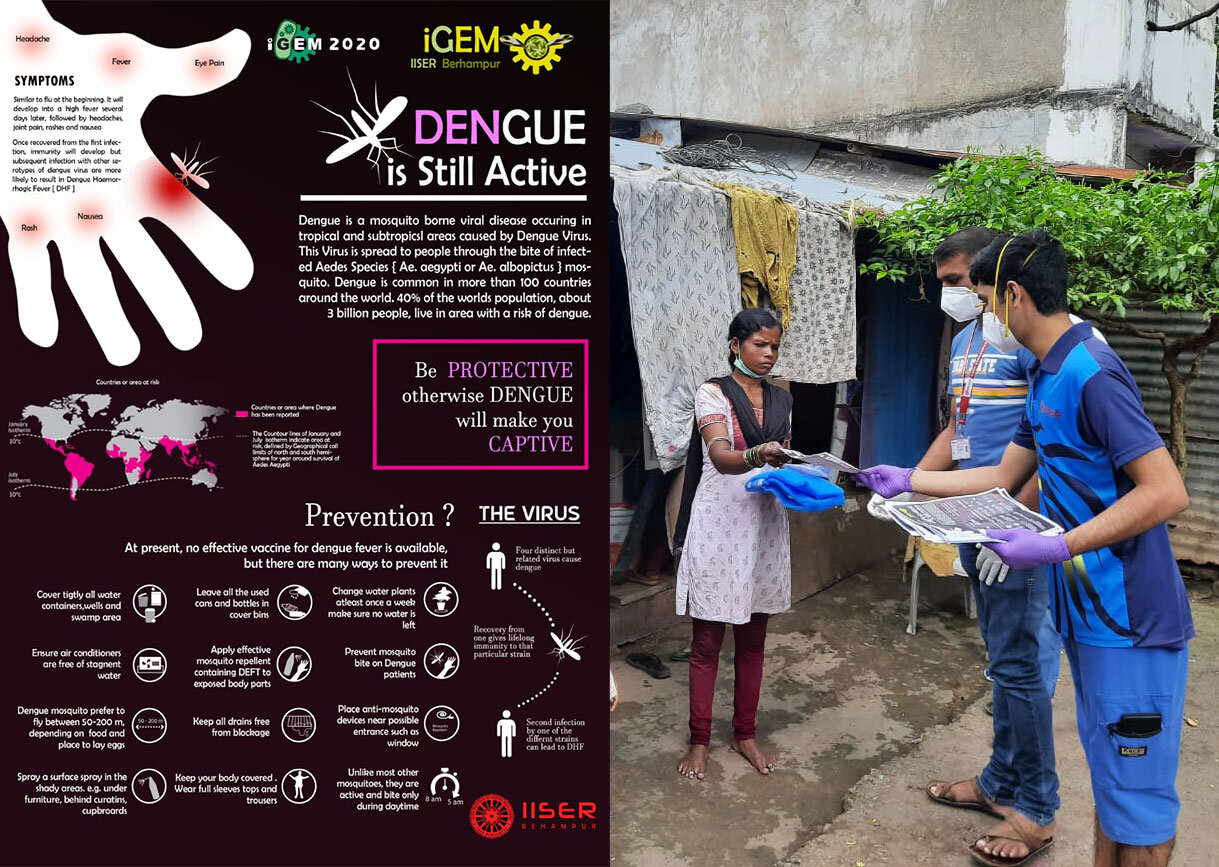

At times, interaction at this stage can inspire impact directly from the stakeholders themselves. For example, Team IISER Berhampur at iGEM 2020 embarked on a mission to create an intervention strategy against Dengue fever. They started by talking with the district medical authorities, and in that light realized the lack of awareness among villagers. The team conducted local and global surveys, interviewed scientists and professionals, and decided to start a crowdfunding campaign in which the collected money was used for the purchase of mosquito nets from the craftsman and distributed to the local community.

Human practices efforts by team IISER Berhampur 2020 inspired them to take action on Dengue fever intervention in their local community.

(2) Stakeholder interaction when conducting research

Your project has kicked off wonderfully and is amassing exciting preliminary data. How could you improve the impact of your early inferences? Behold the stakeholders! Getting feedback on your work and raising awareness of your research are a few of many opportunities that open up during bidirectional engagement with stakeholders. Involving stakeholders here allows you to identify where it is appropriate to give stakeholders power to influence the course of the research project.

This stage of interaction can help you get access to more data. The North American Breeding Bird Survey serves as an excellent example of engaging citizen stakeholders in collecting data for the research problem. Each spring thousands of skilled amateur birders volunteer to participate in the survey to help identify North American bird populations and map untapped routes in the continent.

(3) Stakeholder interaction when final results are available

Engaging stakeholders with the final findings and inferences is the natural next step for most researchers. But now is the time for your team to reap cumulative benefits from on-going interactions with different stakeholders that you have been having since day one! Use jargon-free language, summarize the essence of your work and allow stakeholders to pour in their thoughts. As your project captures the context, needs and interests of stakeholders; inputs and suggestions at this stage would help you by providing a bigger picture to your work and analyze your work along its breadth and depth.

In conclusion, 2-way stakeholder engagement can lead to improved outcomes for conducting Human Practices and fulfilling one of the core purposes of an iGEM project: to make the world a better place. We hope these suggestions will help you improve stakeholder engagement should you choose to make use of it in the HP facets of your work. By connecting your science to the society around you, you will not only improve outcomes for everybody involved but you will most likely find the process more fulfilling along the way.